Policy

Mental Health America (MHA) believes that treating the whole person through the integration of behavioral health[1] and general medical healthcare can save lives, reduce negative health outcomes, facilitate quality care, and promote efficiency and cost savings.

Behavioral health has historically been authorized, structured, researched, financed and regulated differently than general healthcare, and mental health and substance use disorders have been treated both separately from each other and separately from primary care. This historical separation is now generally understood to have been counter-productive to achieving person-centered, comprehensive health goals. Body and mind are inseparable, interdependent, and interactive, and scientific evidence supports the foundational principle of Mental Health America’s advocacy: “There is no health without mental health.”[2]

Integrated care is a promising practice to deal with the fragmentation of the American healthcare system through a team approach.[3] By bringing behavioral health clinicians into general medical settings – especially primary care -- and adding general medical care to behavioral health treatment, better outcomes can be achieved at lower cost.[4]

Consistent with the principle of integration, every child, adult, and family should receive mental health and substance use prevention, early identification, treatment, and long-term support regardless of how and where the person enters the healthcare system. To accomplish this, integration needs to be dramatically increased at the clinical, operational, financial, and policy levels. Thus, for example,

[a]nalysis of National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys from 2003 to 2006 reveals that despite the high prevalence of depression in primary care (10 to 12 percent), screening [was] extremely low at 2 to 4 percent. Current patterns of screening for depression … are not consistent with making health care more patient-centered, efficient, or effective. Improving identification and treatment of depression in primary care is unlikely to change without better integration of mental health services. Payment and other policies that separate mental health from physical health should be changed to better accommodate care for depression in primary care.[5]

MHA believes that integration must eventually involve the entire treatment community and include the full continuum of general health, mental health and substance use treatment services. Providers on both sides of the behavioral and general healthcare interface should receive full and timely information and should follow evidence-based protocols, informed by team practice, in order to identify all of the potential interacting conditions and treatments and treat the whole person.

Eventually, integration will need to go beyond clinical settings, and engage all relevant stakeholders in the community in the promotion of behavioral health.

The Need for Integrated Care

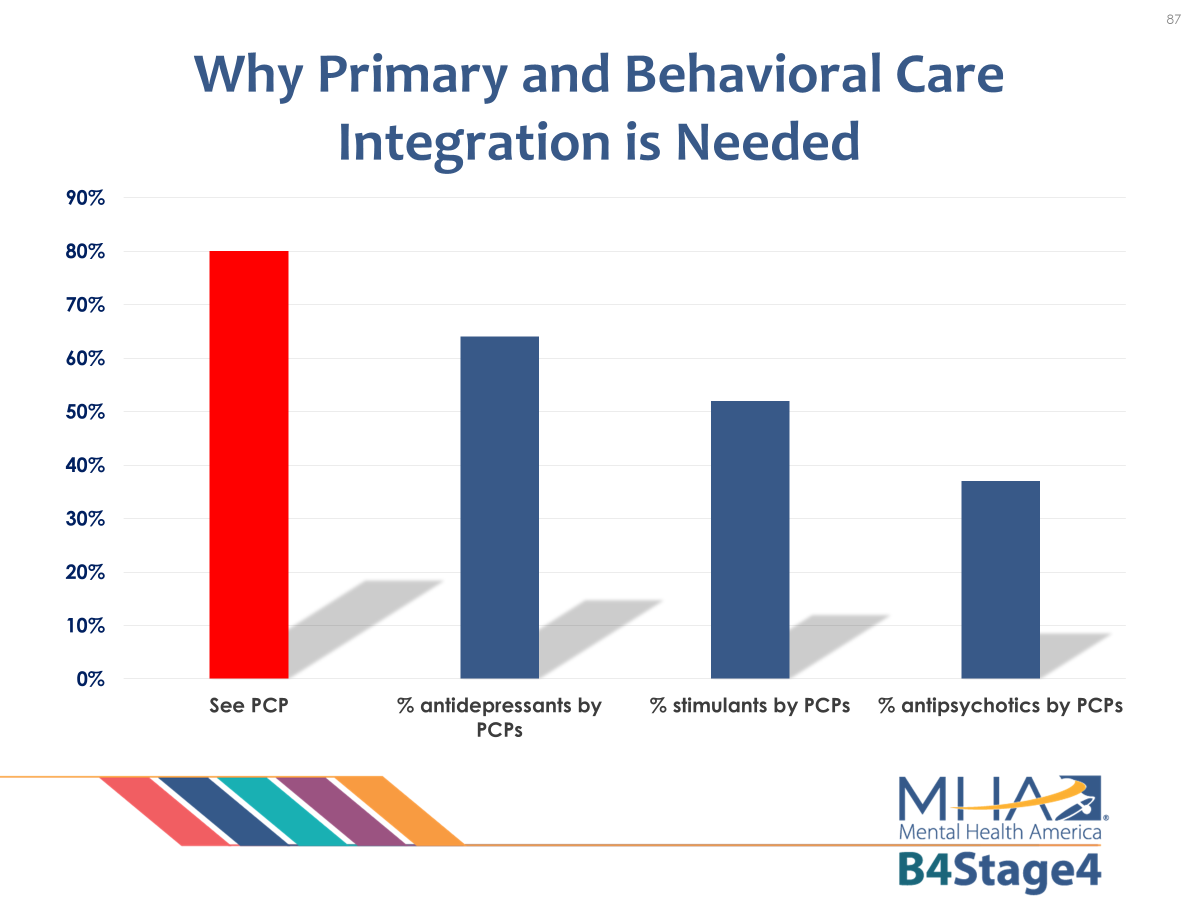

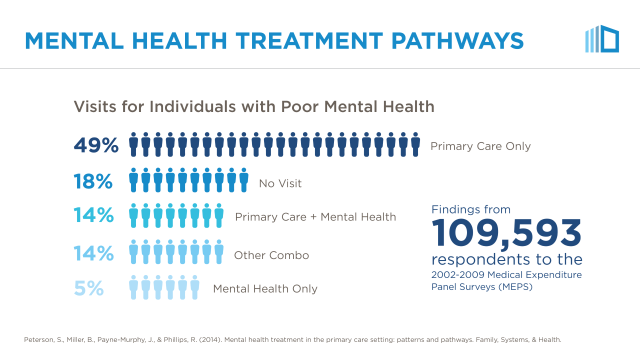

Primary care providers manage care for a large percentage of individuals who are in treatment for behavioral health conditions. Almost 70% of people with poor mental health either do not seek professional help or do so only from their primary care clinician:

Great advances have been made in recent acceptance and elaboration of integrated care through the efforts of the U. S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the U. S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

The need for integration is clear:

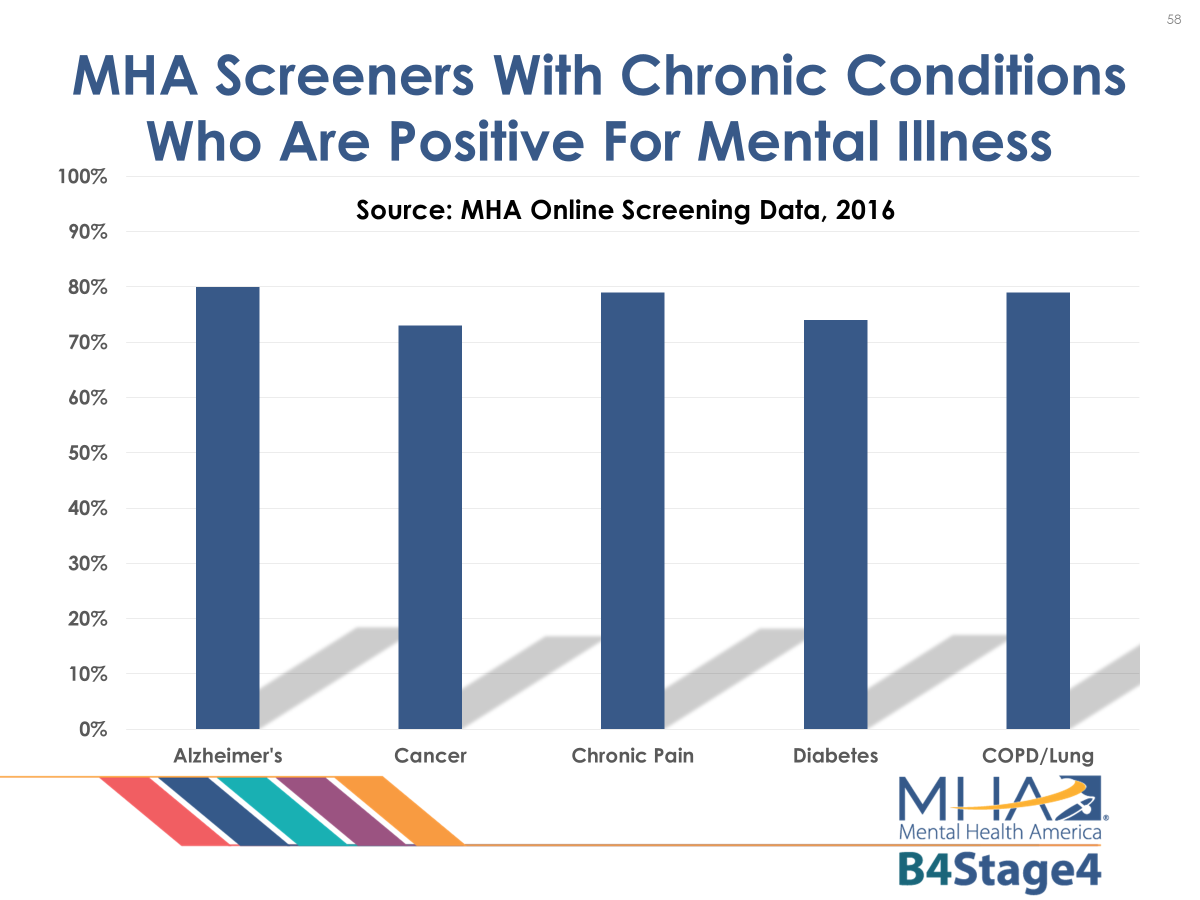

- SAMHSA data from its National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) – 2013 indicates that people with mental illness are, “more likely to have chronic health conditions such as high blood pressure, asthma, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke than those without mental illness. And, those individuals are more likely to use costly hospitalization and emergency room treatment.

- Similarly, people with physical health conditions such as asthma and diabetes report higher rates of substance use disorders and serious psychological distress.

- Depression has emerged as a risk factor for such chronic illnesses as cancer, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes and can adversely affect the course and management of these conditions.”[6]

- A 2017 study of American adolescents showed, “the temporal association of mental disorders and physical diseases in adolescents with mental-physical comorbidity in a nationally representative survey, based on data from 6483 subjects. The most substantial results indicate that affective disorders may increase the risk of arthritis and diseases of the digestive system, that anxiety disorders may increase the risk of skin diseases, and that substance use disorders may decrease the risk of seasonal allergies. Vice versa, heart diseases may indicate a risk of anxiety disorders and any mental disorder, and epilepsy a risk of eating disorders. The clear temporal relationships between mental disorders and physical diseases for specific comorbidity patterns suggest that certain mental disorders may be risk factors of certain physical diseases at early life stages, and vice versa.”[7]

- There is also a growing body of research demonstrating the alarmingly high rates of overall health problems and premature death among individuals with serious mental illnesses. A recent comprehensive review confirmed that people with mental health diagnoses die up to 20 years prior to other individuals with no mental health diagnosis.[8]

- Mental health is essential to overall health and well-being and should be treated with the same urgency as any health condition. Mental illnesses influence the onset, progression, and outcome of other illnesses and often correlate with health risk behaviors such as substance abuse, tobacco use, and physical inactivity.

According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services:

- 50% of Medicaid enrollees have a mental health diagnosis, and Medicaid is the largest payer for mental health services in the United States.

- People diagnosed with mental illness and common chronic health conditions have health care costs that are 75% higher than those without a mental illness diagnosis; for individuals with a co-occurring mental or substance use disorder and common chronic condition, the cost is two to three times higher than what an average Medicaid enrollee pays for health care.[9]

- For those with diabetes, the cost of treating this health condition is as much as four times higher when a co-occurring condition such as depression or alcohol addiction is untreated.”[10]

MHA screening data above (mhascreening.org) for 2016 show how common co-morbidities are in help-seeking populations.

The Implementation of Integrated Care

Integration between behavioral and general healthcare requires both increasing primary care providers’ capacity to address behavioral health conditions and increasing coordination between primary care and behavioral health providers.

Two examples of evidence-based approaches to increasing primary care providers’ capacity to address behavioral health needs are the Collaborative Care Model and the COPE program. The Collaborative Care Model uses behavioral health clinicians as consultants – the primary care provider confers with the behavioral health clinician for advice, but the behavioral health clinician does not necessarily ever meet with each individual face-to-face.[11] Instead, the primary care provider offers evidence-based therapies, medications, and supports through their practice. With the COPE program, a nurse practitioner is trained to deliver a short-course of cognitive-behavioral therapy from within a primary care practice.[12] These two models can work together, and both represent ways of increasing primary care’s capacity to meet behavioral health needs directly. While there are many more examples of how behavioral health can be integrated into primary care, it is critical to design the care model based on a careful assessment of the needs of the surrounding community.[13]

The other approach is to better coordinate primary care and behavioral health providers. In 2010, the U. S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) created the Academy for Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care as a response to the recognized need for a national resource and coordinating center for this type of behavioral health and primary care integration. As behavioral health integration has become more and more of a priority, the demand has increased to collect, analyze, synthesize, and issue actionable information about integration initiatives that providers, policymakers, investigators, and consumers can readily use and apply. AHRQ's Integration Academy exists to “improve the effectiveness and accelerate the pace of making best use of behavioral health in medical care to hit the ‘Triple Aim’ [of improving:] 1) health of populations, 2) experience of care, and 3) reduced per capita cost. (Berwick & IHI, 2008)”[14]

Most significantly, the Academy has developed a compelling definition of integration:

The care that results from a practice team of primary care and behavioral health clinicians, working together with patients and families, using a systematic and cost-effective approach to provide patient-centered care for a defined population. This care may address mental health and substance abuse conditions, health behaviors (including their contribution to chronic medical illnesses), life stressors and crises, stress-related physical symptoms, and ineffective patterns of health care utilization. [15]

This definition requires, in particular:

- A practice team tailored to the needs of each patient and situation [in order t]o create a patient-centered care experience and a broad range of outcomes (clinical, functional, quality of life, and fiscal), patient-by-patient, that no one provider and patient are likely to achieve on their own

- With a panel of clinic patients in common, behavioral health and medical team members together take responsibility for the same shared mission and accountability for total health outcomes.

- Using a systematic clinical approach (and system that enables it to function)

- Involving both patients and clinicians in decision-making to create an integrated care plan appropriate to patient needs, values, and preferences.[16]

Barriers to Integrated Care

The current healthcare system inadequately addresses both sides of the behavioral and general healthcare interface. Barriers such as high caseloads, the burden of billing and documentation, issues with electronic health records and data sharing, lack of financial compensation, lack of education about and familiarity with evidence-based practice, and lack of available time make it difficult for primary health care systems to implement effective behavioral healthcare treatment strategies.[17] Unfortunately, primary care providers often cannot afford the time[18] and thus commonly fail to recognize or treat substance use or mental health conditions.[19] Behavioral health providers suffer some of the same problems in diagnosing and treating general medical conditions.

The responsibility for providing mental health care continues to fall disproportionately on primary care. According to the American Academy of Family Physicians, citing somewhat dated research,[20]

While psychiatric professionals are an essential element of the total health care continuum, the majority of patients with mental health issues will continue to access the health care system through primary care physicians. The desire of patients to receive treatment from their primary care physicians, or at least to have their primary care physicians more involved in their care has been repeatedly documented. Improving mental health treatment requires enhancing the ability of the primary care physician to treat and be appropriately paid for that care. Payment mechanisms should recognize the importance of the primary care physician in the treatment of mental illness as well as the significant issues of comorbidity that require non-psychiatric care.[21]

Supporting Integration into Primary Care

Identifying strategies to reduce the barriers faced by primary care physicians should be a priority since most people in recovery prefer to receive their mental health care within primary care setting. The role of primary care identification and treatment of mental health conditions is also particularly important for special populations including older adults and low-income populations of color that are likely to go undiagnosed.

Some recent policy levers to help scale integration include Section 2703 of the ACA on Medicaid Health Homes. The health home concept and the use of a team approach to treat behavioral and general health conditions show great promise, and integrated healthcare systems enhance the role that social support services and psychosocial treatment play in the recovery process.

Integration has demonstrated improved health status in people in recovery and improved ability of physicians to manage mental health conditions, such as by reduction of emergency room visits.[22] Accumulating evidence supports the effectiveness of some approaches for providing behavioral health care through pediatric primary care. A comprehensive pediatric medical home model that includes behavioral health care has the potential to optimize the availability, quality, benefits, and cost-effectiveness of behavioral health services.[23] Integrated programs such as the chronic care nursing model[24] are effective and cost-efficient for improving the treatment of depression in long term care.[25]

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement, which devised the “Triple Aim,” catalogues successes on its website: http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/ImprovementStories.aspx

Changing the culture of healthcare presents great challenges. Integration, while continuing to show promise, is slow to be implemented in practice. The reasons for this go back to the historical divide between mental health and general healthcare. Substantial organizational and financial barriers persist, and sustainable integrated care programs are still the exception rather than the rule. Health IT remains a mostly undocumented though promising tool. No payment system has been subjected to large scale experiment, and no evidence exists as to which payment mechanisms may be most effective in supporting integrated care.

Outcome studies are promising but not yet persuasive. As summarized in a 2008 AHRQ review, even though “[i]ntegrated care programs have been tested for depression, anxiety, at-risk alcohol, and ADHD in primary care settings and for alcohol disorders and persons with severe mental illness in specialty care settings…, there is no discernable effect of integration level, processes of care, or combination, on patient outcomes for mental health services in primary care settings.[26]

Current Directions in Integrated Practice

In 2016, CMS approved the first set of temporary billing codes in Medicare that allow primary care providers to implement the evidence-based Collaborative Care Model or other models of integrated behavioral health practice.[27] The American Medical Association is expected to finalize permanent billing codes in 2017 or 2018. These new codes afford primary care providers a certain number of minutes a month to coordinate or consult with behavioral health providers, case managers, and the individual to ensure that the individual is receiving effective treatment in primary care. The ability to bill for time spent on integration of behavioral health in primary care offers the opportunity for increased access to mental health and substance use services, and MHA hopes to see Medicaid and private health insurance plans reimburse for these billing codes.

The increased emphasis on behavioral health integration reflects a general movement promoting greater integration across providers and a growing role for primary care in population health management. Across the country, health insurers are forming collaboratives with primary care practices to support shifts and align incentives in primary care to promote better health and lower costs. The Health Care Payment and Learning Action Network’s White Paper Accelerating and Aligning Primary Care Payment Models summarized progress to date, current initiatives, and future principles for primary care transformation.[28] Emblematic of this movement is the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s Comprehensive Primary Care (CPC) Plus model, which is set to commence in 2018. CPC Plus offers primary care providers different levels of payment and incentives based on the needs of the individuals in their practice and how effectively their health is improved.[29] If these incentives are well designed for prevention, early intervention, integrated treatment, and recovery in mental health and substance use, emerging models like CPC Plus may offer primary care greater opportunities for addressing whole person health.

The Future of Integration

There is a growing recognition that health care cannot maximize health on its own – in fact, it is a relatively small determinant of overall health. The National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions in Health and Health Care flagship paper, Systems Strategies for Better Health throughout the Life Course, stated: “Harnessing society’s full potential for optimizing health outcomes across the lifespan requires reaching out well beyond the health care system.”[30] To achieve this aim, the authors call for partnership between stakeholders that include clinicians, health care organizations, pharmacies, people in treatment and their families, social services, public health and safety agencies, schools and preschool facilities, employers, broadcast and social media, consumer product retailers, and law enforcement and the courts. The Eugene S. Farley, Jr. Health Policy Center at the University of Colorado School of Medicine developed a comprehensive 2016 report with recommendations that provide a road map for an integrative future.[31] MHA believes that integration between behavioral health and general health care is only the start. Eventually, behavioral health will need to be integrated across sectors to maximize life-course and population health. While policies increasingly require each sector to work collaboratively, financing policies will need to be changed to provide greater incentives for stakeholders to work together to promote behavioral health.

Call to Action

Mental Health America is dedicated to supporting national, state, and local efforts to integrate behavioral and general health care and to continued efforts to improve the quality of mental health and substance use services available in primary health care settings and the quality of primary health care services available in specialty mental health care settings. Our goal is to foster the broad implementation of available research and models in real-world health delivery systems, and to eliminate the clinical, financial, policy and organizational barriers to the integration of mental and general health care. To this end, MHA calls on advocates to promote the following policies:

- Payment policies, quality measurements, and practice guidelines should include behavioral health screening with other routine screenings, such as blood pressure screening for adults and vision and hearing screening for children, in all health care settings.

- All health insurers, including Medicaid, should cover the Collaborative Care Model and general behavioral health integration billing codes, as well as related codes for behavioral health prevention, early intervention, treatment, and care management/coordination.

- Advanced primary care models, including Comprehensive Primary Care Plus, should include risk of mental health and substance use conditions in its risk adjustment formula, and include outcomes related to prevention, screening, and progress toward remission in its quality measurement and value-based payment framework to ensure that primary care has maximum incentives to act as the care team quarterback for supporting each individual in their recovery.

- Payers should also include behavioral health providers and outcomes related to prevention, screening, and progress toward remission in their quality measurement and value-based payment frameworks for multi-practice payment arrangements, such as Accountable Care Organizations or Patient-Centered Medical Home Neighborhoods.[32]

- Psycho-social, recovery-oriented and rehabilitation services should be included in accreditation or recognition standards for advanced primary care to effectively address behavioral health conditions in an integrated setting, including use of peer support specialists on care teams.

- The federal government should facilitate inclusion of integrated behavioral health services into both public and private programs and streamline approval mechanisms. Once proven successful via Medicaid waiver in one state, other states should not be required to go through a full waiver process to incorporate them into their own Medicaid programs.

- The federal government should place requirements and quality measures related to effective behavioral health integration into all of its grant programs, information technology, and policies.

- The federal government and states should increase incentives for behavioral health providers to reach Health Information Technology Meaningful Use standards.

- Capacity for Electronic Health Record (EHR) sharing should be greatly increased and built into all federal and state grants and technical assistance, and barriers to sharing information among health and behavioral health providers should be reduced through conforming 42 CFR Pt. 2 (dealing with substance use identification and treatment) to HIPAA. Data collected in EHRs should measure and report information and outcomes that matter most to individuals dealing with behavioral health concerns.

- MHA supports the development of personalized care management and communication tools that include all transitional and care plans developed for an individual. These tools should be in the control of the individual. When appropriate, case managers should coordinate the transfer of information in the tools on behalf, and at the direction, of individuals as they move from one care setting to another.

- The private sector should be encouraged to share its experience with care coordination in order to help foster the growth of integration in all healthcare systems, especially in the context of multi-payer collaboratives.

- Initiatives like “Flip The Clinic” should be scaled up to find new person-centered and design-oriented ways to better integrate behavioral health and meet the needs of individuals at risk of or dealing with mental health and substance use conditions.

- States and local authorities should foster community coalitions and multi-payer/provider collaboratives to promote integration models that address their communities' unique needs.

- Provider education and training should prepare students for integrated care settings and respond to the changing incentives of whole-person, integrated health care.

Effective Period

This policy was approved by the Mental Health America Board of Directors on June 13, 2017. It is reviewed as required by the MHA Public Policy Committee.

Expiration: December 31, 2022

Top of Form

[1] Behavioral healthcare has become a common collective term for treatment of mental health and substance use conditions, and integration of the two treatment systems, eliminating the silos that separate them, is an important MHA objective. However, Congress has still not acted to conform 42 CFR Pt. 2 (dealing with substance use identification and treatment) to HIPAA, in part because substance use treatment is still largely separated from other healthcare systems in practice, and few studies of substance use integration with primary care are available. See, e.g., Savic, M.,, Best, D., Manning, V. & Lubman, D, “Strategies to Facilitate Integrated Care for People with Alcohol and Other Drug Problems: A Systematic Review,” Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 12(1):19 (2017). doi: 10.1186/s13011-017-0104-7:

“The major focus of the literature on the effectiveness of integrated care for people with AOD problems has been around the integration of AOD and mental health care. With some exceptions, systematic reviews of empirical studies generally report that clients receiving integrated care report improved AOD and/or mental health outcomes and higher satisfaction with treatment than clients receiving standard treatment. Similarly, randomized trials evaluating the effectiveness of the integration of AOD and medical care have found higher rates of abstinence from AOD without adding significant additional costs amongst clients receiving integrated care. Further evidence suggests that integrated medical and AOD care may confer long-term benefits in terms of medical, wellbeing and functioning outcomes six months after treatment [24] and up to nine-years post-treatment entry.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28388954

[2] McLeod, S. A. (2007). “Mind Body Debate,” www.simplypsychology.org/mindbodydebate.html

[3] The Mayo Clinic and Kaiser Permanente are often cited as examples of such an approach. Definitions can help clarify terms:

- Coordinated care Behavioral health and primary care clinicians practice separately in their own systems and facilities, but often work together through telephone, on-line, or other communication systems to exchange information.

- Colocated care Behavioral health providers are located within primary care settings, and deliver behavioral health care in the primary care clinics. A common treatment plan or framework to integrate behavioral health and primary care is not present.

- Integrated care Behavioral health services are included as part of primary care using tightly integrated on-site teamwork, in which behavioral health and primary care services are available to all patients and often subsumed within a common framework.

- Collaborative care Team-based care involving a partnership between behavioral health and primary care clinicians, and patients and families involving a shared treatment plan. (http://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care )

[4] Balasubramanian, B.A., Cohen, D.J., Jetelina, K.K., et al., “Outcomes of Integrated Behavioral Health with Primary Care,” The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 30(2):130-139 (2017), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28379819 ; Melek, S.P., Norris, D.T. & Paulus, J., “Economic Impact of Integrated Medical-Behavioral Healthcare: Implications for Psychiatry” (2015), a report by Milliman, Inc., a global consulting and actuarial firm, commissioned by the American Psychiatric Association and published online by the AHRQ Integration Academy, https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov

[5] Phillips, R. L., Jr., Miller, B. F., Petterson, S. M., & Teevan, B., “Better Integration of Mental Health Care Improves Depression Screening and Treatment in Primary Care,” Am Fam Physician 84(9):980 (2011), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22046936 . (emphasis supplied).

[6] Centers for Disease Control website, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5434a1.htm

[7] Tegethoff, M., Stalujanis, E., Belardi, A. & Meinlschmidt, G., “Chronology of Onset of Mental Disorders and Physical Diseases in Mental-Physical Comorbidity - A National Representative Survey of Adolescents,” PLoS One. 2016 Oct 21;11(10):e0165196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165196. eCollection (2016).

[8] Chesney, E., Goodwin, G.M. & Fazel, S., “Risk of All-Cause and Suicide Mortality in Mental Disorders: A Meta-Review,” World Psychiatry 13(2):153-60 (2014). doi: 10.1002/wps.20128. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24890068

[9] See also, Petterson, S., et al., "Why there must be Room for Mental Health in the Medical Home," American Family Physician 77(6): 757 (2008), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18853532 .

[10] SAMHSA website, “Health Care and Health Systems Integration,” https://www.samhsa.gov/integrated-health-solutions

[13] Balasubramanian, B. A., et al., op. cit. (2017), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28379819

[16] The definition is fully detailed, id. at 3-4. These are the salient elements (emphasis supplied).

[17] Kathol, R. G., Butler, M., McAlpine, D. D., & Kane, R. L., “Barriers to Physical and Mental Condition Integrated Service Delivery,” Psychosom Med, 72(6):511-518 (2010). doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e2c4a0, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20498293

[18] Miller, B. F., Teevan, B., Phillips, R. L., Petterson, S. M., & Bazemore, A. W., “The Importance of Time in Treating Mental Health in Primary Care,” Families, Systems & Health : the Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare, 29(2):144-145 (2011). doi:10.1037/a0023993, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21688905 .

[19] Phillips, R. L., Jr., et al. "Better Integration of Mental Health Care Improves Depression Screening and Treatment in Primary Care." Am Fam Physician 84(9): 980 (2011); American Psychiatric Association news release (February 15, 2017), http://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/depression-screening-rates-in-primary-care-remain-low

[20] Gallo, J.J. & Coyne, J.C., “The Challenge of Depression in Late Life: Bridging Science and Service in Primary Care,” JAMA 284(12):1570-1572 (2000), http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/193106 ; Williams, J.W. Jr., “Competing Demands: Does Care for Depression Fit in Primary Care?” J Gen Intern Med 13(2):137-139 (1998), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1496916/ . More recent research confirms these findings. See, e.g., Petterson, S., et al., "Mental Health Treatment in the Primary Care Setting: Patterns and Pathways." Families, Systems, & Health 32(2): 157-166 (2014), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24773273 .

[21] AAFP Position Paper: “Mental Health Care Services by Family Physicians,” undated and unnumbered, retrieved March 13, 2017. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/mental-health-services.html

[22] Kim, J.Y., Higgins, T.C., Esposito, D. & Hamblin, A., “Integrating Health Care for High-Need Medicaid Beneficiaries with Serious Mental Illness and Chronic Physical Health Conditions at Managed Care, Provider, and Consumer Levels,” Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2017 Feb 9 (2017). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28182472 doi: 10.1037/prj0000231. [Epub ahead of print]

[23] Asarnow, J.R., Kolko, D.J., Miranda,J. & Kazak, A.E., “The Pediatric Patient-Centered Medical Home: Innovative Models for Improving Behavioral Health, American Psychologist 72(1): 13–27 (2017), https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/amp-a0040411.pdf

[25] Davis, M.J., Moore, K.M., Meyers, K., Mathews, J. & Zerth, E.O., Engagement in Mental Health Treatment Following Primary Care Mental Health Integration Contact, Psychol Serv. 13(4):333-340 (2016). Epub 2016 May 30, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27243110 .

[26] AHRQ Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 173 (2008), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK38632/